What did the Prime Minister say?

As the economic shockwaves from the Covid-19 pandemic continues to permeate throughout the globe, Australia looks ahead to the future. A determined Scott Morrison delivered a patriotic speech at the National Press Club on Tuesday, 26 May. The message was clear: Australia is on the mend, but we must pull through together.

The Prime Minister used a collaboration of populist and patriotic expression to quell fears of uncertainty for the future. The speech riddled with nationalistic undertones praised Australians for their grit, courage and resilience through a turbulent year. Whilst many will view this rhetoric as necessary in order to bring the nation together to combat the biggest economic challenge since the Great Depression. A small minority can view this as ‘papering over the cracks’ and a whimsical plea to maintain harmony until a concrete plan for economic action is implemented.

What are the goals?

Nonetheless, the Prime Minister did outline his ambitious objectives for the short-medium term. Drawing upon the unanimous support from key influential figures in federal politics including the Treasurer, Deputy PM and leader of the Senate. The PM revealed that his government’s focus would be on industrial relations; as the key to rebuilding the fragile economy. He will chair five working groups for discussions to produce a ‘JobMaker’ package. On the list of discussions include award simplification, fundamental enterprise agreement-making, Fair Work Commission reviews on casual and fixed term employees, compliance and research into ‘greenfield’ agreements for new enterprises.

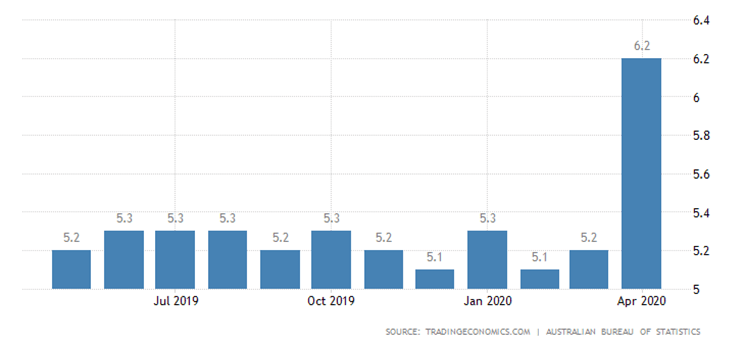

Why the focus onAustralian jobs and industrial reform? Is it to increase employment and helps the millions (circa 2 million) of Australians out of a job to curb the surging unemployment rate? Is ScoMo genuinely trying to give “a go for those who have a go”? Whilst all these reasons will be publicly promoted as the main reasons for the creation of JobKeeper and JobSeeker. The opposition will argue the government is glorifying its achievements. However, as is often the case in national politics, there is a simple economic reason for the salience of labour market reform and business cash splashes from the government.

Stabilisation or liberalisation?

To understand the agenda of the government, it is important to analyse the economic and political tools at the executive’s disposal during these uncertain times. As clearly demonstrated by his national speeches, the PM has utilised patriotic sentiment and nationalist wordage (this is most evident in his over-used platitude` “how good are Australians?”) to stabilise the population. Majority of political pundits will agree that this has worked effectively, despite the ‘mass buying’ hysteria during the initial phases of the pandemic. Certainly, compared to highly liberalised nations like the U.S, Australia has been quite passive with little organised movements against lockdowns and quarantine. We can mark this as a win for the government.

Since the Australian public is stable and social institutions are still operating relatively well despite abnormal societal conditions. The Federal Government can begin to dig deeper into its bag of tricks to commence the long and argues economic turnaround.

The Economic Options: The Centre-Right Playbook

The government has two macroeconomic policy tools, fiscal and monetary, that are commonly used in the event of a systemic shock, just like Covid-19. These tools are ‘stabilisers’ that are aimed to prevent the economy of ‘overheating’ in booms or underperforming in periods of decline. The right-wing Liberal party is founded on the ideals of ‘small government’ and market-based solutions. Henceforth, the government has utilised ‘fiscal consolidation’, in other words, minimalised discretionary spending in order to produce a budget surplus. As seen in the pandemic, welfare-state policies such as JobSeeker and JobKeeper are often seen as a last resort and primarily used to keep businesses afloat. This can be seen by the design of JobKeeper, which is primarily provided to businesses that have experienced a significant drop in revenues.

Due to the costs of such large fiscal policies, the right-wing politics of the current cabinet is unlikely to pursue similar programs such as a JobSeeker for the foreseeable future. (In fact, it is expected to expire without renewal in September). The reluctance to utilise the excess $60 billion from the accounting error in late May is only further proof of the right-wing ‘debt hawk’ stance. Therefore, we can expect large social programs such as JobSeeker to remain an exception to the rule.

Why not interest rates?

Since fiscal policy is an unlikely source of economic stabilisation, one may turn to interest rates (or monetary policy for those who like economic jargon). Interest rates are a great macroeconomic tool that aims to control inflation, credit supply and stabilise unemployment. The basic theory is that it is a transmission mechanism, managed by the RBA as an independent actor from the federal government. The RBA will use the purchase/sale of government securities to shift the cash rate. However, the cash rate has reached historical lows at 0.75% prior to the pandemic. In response to the crisis, it was lowered to 0.25% in a counter-cyclical effort to promote consumer expenditure, reliable credit and business/investor confidence.

This may be effective in the short-term, but what will the RBA do in the medium term? The rates cannot go any lower as we have hit the proverbial ‘zero low bound’. Whilst the ECB (European Central Bank) has experimented with negative interest rates, the norm certainty suggests this is an outlier. Hence, the RBA will employ extreme caution and avoid lowering rates any further, which has been indicated by Phillip Lowe. The same can be predicted for financial institutions, whom rely on a healthy interest rates spread for profit. Therefore, the mystical powers of interest rates are far less appealing in the eyes of a cautious government.

Why Industrial Reform?

As a result, the PM has limited options in the federal economic arsenal. Where does the government turn to vitalise the expected and needed economic revival? The answer is simple and easy to promote to the public. Microeconomic reform. Or more simply… cut industry tape and create jobs.

Microeconomic reform transcends a range of domains in the economy. It is mostly associated with the reduction of ‘red tape’ in the production process through the division of labour. Workers (labour) specialise in their most efficient activity, theoretically each worker becomes more productive and thus engenders greater output. This is reflected by a higher wage as the worker becomes more valuable. The Prime Minister plans to implement this basic economic ideology on multiple fronts, condensed into the proclaimed ‘JobMaker’ package.

What can we expect?

The expectation is the government will invest in vocational training that provide skills that are required for specific jobs in the ‘new’ digital economy. TAFE courses will become cheaper and more abundant, as Australians will be encouraged to become more productive. Flexible workplace options will become the norm such as ‘working from home’ and ‘flexi hours’ that effectively reduce the burdens of travel and brick & mortar that erode productivity. Universities will also benefit from an influx of domestic students to offset the loss of international students.

On the state government level, firm-specific leakages such as the payroll tax will most likely be abolished as a means to alleviate the financial distress of the small-medium enterprises. The expectation that rational owners and entrepreneurs redistribute these savings to improve the efficiency of their businesses.

The Final Verdict

The opposition will argue that the microeconomic policy approach very approach is not conservative for a ‘small government’ that the Liberal party embody. However, the Liberal party understand that microeconomic policy is underpinned by the Keynesian belief that such reform will increase the long-term supply capacity of the economy. As such, the intertemporal benefits outweigh the numerical investment. Therefore, those with a keen political eye may view the approach as a ‘pseduo-fiscal’ policy designed to improve confidence of the working class to spur consumerism. Either way, the incumbent government has an uphill political battle on its hands. These policies are a long-term play in a word of myopic ideologies. So this begs the question… will Scott Morrison survive the upcoming ideological war without a strong economy to stand upon?

Daniel Dell’Armi