Overview

Healthcare in the United States is classified as a consumer product and not a universal constitutional or legal right. The system is a hybrid model that incorporates an uneven balance between the elements of privatised and public networks. The burden of responsibility for government supervision the is divided into primarily the federal and state level with minimal involvement from local authorities. However, the main point of separation exists in the marketplace for insurance. The private sector utilises an ‘employer-facing’ scheme that provides a substantial amount of purchasing power to privatised entities such as pharmaceutical companies, private hospital providers, commercialised ‘extras’ options and managed care organisation. Whereas the government sphere funds various welfare schemes for disadvantaged consumers with pre-existing conditions and primitive access to jobs, and proportionally distributes federal and state taxpayer money into public infrastructure. Both realms of the system significantly limit the options, opportunities, affordability and coverage for consumers. The introduction of the colloquially coined term, ObamaCare, in 2014 introduced measures to alleviate these limitations. However, further micro-economic reforms are required to increase the competitiveness of the public sector, increase the power of middle-class consumers in the private insurance market and curb the influence of private firms in the industry.

Structure

The healthcare infrastructure is an amalgamation of taxpayer bureaucratic funding and privatised investment. The private infrastructure is funded through venture capitalists, charitable donations, shareholders and private insurance. Hospitals, mental institutions, dentists and other ‘extras’ options are all included in this sphere. The access to these services is limited to paying customers, either through an insurance plan or direct cash basis. The shortfall between the amount covered by insurance and the total price levied by the private entity is called the ‘out-of-pocket’ sum for consumers. Traditionally, those in the upper middle-class or elitist societal classes can afford this form of healthcare through their employers or direct purchase in some cases. The inelastic nature of medicine allows providers to charge relatively high prices without the fear of deadweight loss. This profitability is a key contributor to the expansion of the private market into a commercialised force that induces incredibly elevated prices that often do not match the true market-clearling equilibrium. Therefore, the producer surplus significantly exceeds the consumer surplus in the healthcare market. This represents a fundamental problem for an industry that is designed to altruistically create positive externalities for consumers rather than producers. Hence, it is lucid that the capitalistic framework of the private sector has lead to the unfair distribution of healthcare in the country.

Inefficiencies of the Public System

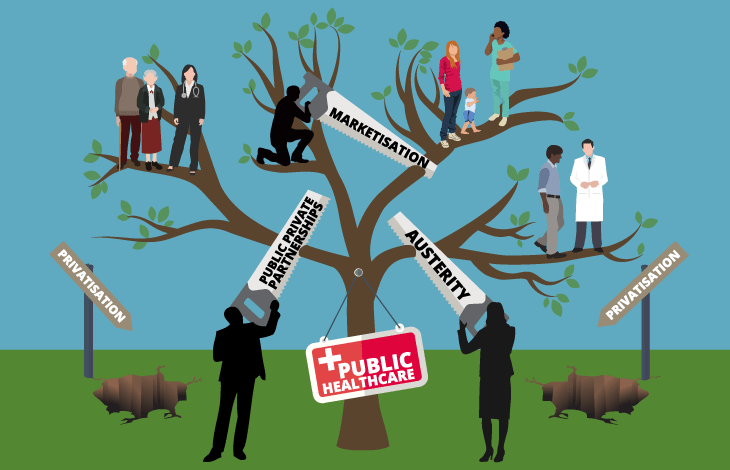

Moreover, the public infrastructure acts as a ‘safety net’ for those that cannot afford access into privatised services. Public entities cannot refuse entry to uninsured or impoverished members of society. Thenceforth, the lack of privatised pricing models such as hospital and ambulances fees prevent public administrators from developing their infrastructure, thus resulting in poor and limited services for consumers. Therefore, since the majority of healthcare providers are unanimously members of the private sector, the public sector is slowly degrading due to the lack of a comparative advantage with private sector entities. Hence, this represents a need for substantial government intervention in order to curb the negative externalities of limited access of important medical products for disadvantaged people. However, the need for this intervention is often nixed by the libertarian elements of the population due to the values of civil liberty, individual property rights and capitalist notions. As a result, the market has become an oligopoly through the carterlisation of pharmaceutical companies that leverage the ‘lobbying’ of government bodies to ensure prices remain high. The academic idea of the Nash Equilibrium in the economic subsect of Game Theory supports this strategy as a sound profit-maximising expedition that can only further escalate the profits of these private firms. The absence of sufficient anti-trust laws is a significant obstacle to reduce the control of corporate entities in the market. Therefore, it can be seen that private lobbying, inefficient government structures and internal bureaucracy has disallowed the government from efficiently implementing policy to maximise healthcare coverage for the population.

The Role of the Private Market

Clearly, the financial backbone of the healthcare system is the privatised insurance market. This derivative industry provides more than half of the American population with insurancethat can be used in hospitals, mental institutions, dentists and other non-emergency entities. The salient consumer in the primary market for private healthcare is employers. Firms that hire labour throughout the nation purchase various forms of insurance policies in bulk due to the benefits of tax deductibility. Employees are then permitted to provide these healthcare plans as part of their renumeration package for joining the employer’s company. As a result, consumers do not have full visibility of their purchase and possess limited options for alternatives as it is unlikely for an employee to work simultaneously at two firms. Therefore, since substitute goods are not available, prices for these insurance options are relatively high with lower quality. Alternatively, the federal government through its progressive income taxation system funds various ‘welfare’ programs that are designed to provide cover for those that are considered classified as a disadvantaged. Henceforth, the public option is limited to those that are arbitrarily ‘at-risk’, which includes the proportion of the population that possess ‘pre-existing conditions’ that diminish the ability to access private insurance and/or eligible for military or public service schemes (such as CHIPS). Medicare, Medicaid and Veterans Schemes are the most notable of these public services. However, these services have strict eligibility requirements that are sometimes annually reviewed by the relevant federal (primarily the Department of Health and Human Services) government departments. Consequently, a substantial percentage of the population is left uninsured as they are freezed out of the private insurance market due unemployment or voluntary labour force omission and the inability to place themselves into a category that is eligible for welfare benefits. Ergo, unlike the majority of erstwhile developed countries, the fact that healthcare is fundamentally not considered a right, means that the government is not liable to cover for the healthcare of the residual Americans that are left uninsured in this two-paced system.

Does ObamaCare work?

The progressive coalition of the Obama administration sought to rectify the universality issues of the healthcare system. The legislative and executive branches identified that the fundamental vacuum of responsibility from the federal government to cover the majority of Americans ought to be resolved. Hence, the Affordable Care Act 2010, ACA) passed Congress, colloquially known as ObamaCare, aimed to reduce the numbers of uninsured due to pre-existing conditions. The core feature that symbolically represented an incremental shift towards the universality of healthcare rights was the introduction of the ‘individual mandate’. Despite being later removed under the Trump administration in its populist revolt against progressivism, it ensured that individuals would choose an insurance scheme, or otherwise face a monetary penalty. On a macro-economic level, the creation of a Healthcare Marketplace (or exchange) that attempted to remove barriers for consumers to enter the private healthcare market. This market essentially allowed employees to bypass the ‘employer-facing’ market that dominated the system since the 1920s. The simple idea that the increase in the numbers of consumers in the market would result in a positive shift in the supply of insurance, would decrease the price for insurance providers as the unsystematic risk is divided over a larger population of insured members. However, the state-based exchanges are regulated by federal government bodies including the Centres for Medicaid and Medicare Services through interventionist market forces (price controls, subsidies, quotas etc). These policies act as cost constraints to reduce the prices for lower-income families and individuals with pre-existing conditions. The ‘red tape’ has the unintentional of premium increases as the ‘cost controls’ through price ceilings (such as capping providers rates for those on Medicare and Medicaid, and fixed negotiated medicinal prices) decrease the revenue for private providers and insurance firms. Therefore, it can be seen that whilst the marketplace initiative is quintessentially a solid strategic plan in expanding the coverage of healthcare, it is also only a primitive solution in creating provider flexibility, choice, affordability and competition in the primary markets.

How can it be improved?

Whilst ObamaCare is not the perfect solution to the coverage and pricing issues in the system, it is a solid stepping stone for future reform. The core problem with the current setup of ObamaCare is the centralised exchange (marketplace) mechanism that attempts to consummate government schemes such as MediCare with an open market instrument. The exchange should retain its integrity as an alternative option for consumers to purchase insurance, rather than relying on employers to provide such healthcare. However, pricing controls such as subsidies, negotiated medicinal prices and caps on ‘out-of-pocket’ expenses should be removed from its boundaries. The sole purpose of this marketplace is to provide an alternative for consumers that are forced into purchasing sub-prime insurance from employers. This marketplace should provide options and opportunity to obtain cheaper insurance through real market competition, rather than manufactured price. Therefore, the federal government should focus on the development of an alternative public sector marketplace that will contain the aforementioned government programs like Medicaid, CHIPS and alternative Veteran services. The creation and implementation of state-based healthcare policies that are relatively cheaper than private options for superior public healthcare services would provide the unparalleled market competition. As a result, displaced consumers can access this market with minimal monetary barries. This will essentially disrupt the cartel formation in the provider market as the government becomes an additional competitor. Since the ‘visible hand’ or ‘social benefactor’ has the advantage of tax-payer funds (equivalent to private donorship for private insurance and infrastructure). These ‘public option’ programs will be exchanged in an independent ACA exchange that all Americans can access directly. Henceforth, this market would compromise of a bucketload of substitute products that can compete with the excessive prices in the private sector. State governments would then have the leverage to negotiate medicinal prices with providers and re-direct the additional revenue to the development of public hospitals and infrastructure. In order to maintain the ‘checks and balances’, the federal government would become the independent regulator of both exchanges through the implementation of neutral bodies that provide oversight to avoid conflict of interests. Resultantly, the formation of this ‘two-fold exchange’ system is the optimal step into the harmonisation of the public and private systems.

What now?

In summary, the current state of the United States healthcare system is a convoluted leviathan of capitalistic private privileges and defunctive public options. The primitive options for consumers (employees) in the private insurance market is astounding, carterlisation of basic medical products and elitist segregation of private healthcare infrastructure are notable symptoms of a greedy system. The public option fails to provide a sufficient ‘safety net’ for residual members of society due to funding constraints, limited government welfare programs and the inability to centralise the offerings into a succinct marketplace. Whilst ObamaCare has made positive steps into expanding coverage, the integrated cost controls and public options into the private market is inefficient and causing market failure. The optimal microeconomic reform is the introduction of an exclusive public marketplace for existing welfare programs and additional ‘out-of-pocket’ policies that can rival the incumbent plans in the private market. This would provide competition to the over-priced healthcare plans and allow state governments greater power to negotiate with providers in the long-term.

By Daniel Dell’Armi